JPEG 2000

Comparison of JPEG 2000 with the original JPEG format. |

|

| Filename extension | .jp2, .j2k, .jpf, .jpx, .jpm, .mj2 |

|---|---|

| Internet media type | image/jp2, image/jpx, image/jpm, video/mj2 |

| Uniform Type Identifier | public.jpeg-2000 |

| Developed by | Joint Photographic Experts Group |

| Type of format | graphics file format |

| Standard(s) | ISO/IEC 15444 |

JPEG 2000 is an image compression standard and coding system. It was created by the Joint Photographic Experts Group committee in 2000 with the intention of superseding their original discrete cosine transform-based JPEG standard (created in 1992) with a newly designed, wavelet-based method. The standardized filename extension is .jp2 for ISO/IEC 15444-1 conforming files and .jpx for the extended part-2 specifications, published as ISO/IEC 15444-2. The registered MIME types are defined in RFC 3745. For ISO/IEC 15444-1 it is image/jp2.

Contents |

Aims of the standard

While there is a modest increase in compression performance of JPEG 2000 compared to JPEG, the main advantage offered by JPEG 2000 is the significant flexibility of the codestream. The codestream obtained after compression of an image with JPEG 2000 is scalable in nature, meaning that it can be decoded in a number of ways; for instance, by truncating the codestream at any point, one may obtain a representation of the image at a lower resolution, or signal-to-noise ratio – see scalable compression. By ordering the codestream in various ways, applications can achieve significant performance increases. However, as a consequence of this flexibility, JPEG 2000 requires encoders/decoders that are complex and computationally demanding. Another difference, in comparison with JPEG, is in terms of visual artifacts: JPEG 2000 produces ringing artifacts, manifested as blur and rings near edges in the image, while JPEG produces ringing artifacts and 'blocking' artifacts, due to its 8×8 blocks.

JPEG 2000 has been published as an ISO standard, ISO/IEC 15444. As of 2010[update], JPEG 2000 is not widely supported in web browsers, and hence is not generally used on the World Wide Web.

Features

- Superior compression performance: at high bit rates, where artifacts become nearly imperceptible, JPEG 2000 has a small machine-measured fidelity advantage over JPEG. At lower bit rates (e.g., less than 0.25 bits/pixel for grayscale images), JPEG 2000 has a much more significant advantage over certain modes of JPEG: artifacts are less visible and there is almost no blocking. The compression gains over JPEG are attributed to the use of DWT and a more sophisticated entropy encoding scheme.

- Multiple resolution representation: JPEG 2000 decomposes the image into a multiple resolution representation in the course of its compression process. This representation can be put to use for other image presentation purposes beyond compression as such.

- Progressive transmission by pixel and resolution accuracy, commonly referred to as progressive decoding and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) scalability: JPEG 2000 provides efficient code-stream organizations which are progressive by pixel accuracy and by image resolution (or by image size). This way, after a smaller part of the whole file has been received, the viewer can see a lower quality version of the final picture. The quality then improves progressively through downloading more data bits from the source. The 1992 JPEG standard also has a progressive transmission feature but it's rarely used.

- Lossless and lossy compression: Like Lossless JPEG,[1] the JPEG 2000 standard provides both lossless and lossy compression in a single compression architecture. Lossless compression is provided by the use of a reversible integer wavelet transform in JPEG 2000.

- Random code-stream access and processing, also referred as Region Of Interest (ROI): JPEG 2000 code streams offer several mechanisms to support spatial random access or region of interest access at varying degrees of granularity. This way it is possible to store different parts of the same picture using different quality.

- Error resilience: Like JPEG 1992, JPEG 2000 is robust to bit errors introduced by noisy communication channels, due to the coding of data in relatively small independent blocks.

- Flexible file format: The JP2 and JPX file formats allow for handling of color-space information, metadata, and for interactivity in networked applications as developed in the JPEG Part 9 JPIP protocol.

- Side channel spatial information: it fully supports transparency and alpha planes.

More advantages associated with JPEG 2000 can be referred to from the Official JPEG 2000 page.

JPEG 2000 image coding system - Parts

The JPEG 2000 image coding system (ISO/IEC 15444) consists of following parts:

| Part | Number | First public release date (First edition) | Latest public release date (edition) | Latest amendment | Identical ITU-T standard | Title | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part 1 | ISO/IEC 15444-1 | 2000 | 2004 | 2006[4] | T.800 | Core coding system | the basic characteristics of JPEG 2000 compression (.jp2) |

| Part 2 | ISO/IEC 15444-2 | 2004 | 2004 | 2006[5] | T.801 | Extensions | (.jpx, .jpf) |

| Part 3 | ISO/IEC 15444-3 | 2002 | 2007[6] | T.802 | Motion JPEG 2000 | (.mj2) | |

| Part 4 | ISO/IEC 15444-4 | 2002 | 2004[7] | T.803 | Conformance testing | ||

| Part 5 | ISO/IEC 15444-5 | 2003 | 2003 | 2003[8] | T.804 | Reference software | Java and C implementations |

| Part 6 | ISO/IEC 15444-6 | 2003 | 2003 | 2007[9] | Compound image file format | (.jpm) e.g. document imaging, for pre-press and fax-like applications | |

| Part 7 | abandoned[2] | Guideline of minimum support function of ISO/IEC 15444-1[10] | (Technical Report on Minimum Support Functions[11]) | ||||

| Part 8 | ISO/IEC 15444-8 | 2007 | 2007 | 2008[12] | T.807 | Secure JPEG 2000 | JPSEC (security aspects) |

| Part 9 | ISO/IEC 15444-9 | 2005 | 2005 | 2008[13] | T.808 | Interactivity tools, APIs and protocols | JPIP (interactive protocols and API) |

| Part 10 | ISO/IEC 15444-10 | 2008 | 2008 | 2008[14] | T.809 | Extensions for three-dimensional data | JP3D (volumetric imaging) |

| Part 11 | ISO/IEC 15444-11 | 2007 | 2007[15] | T.810 | Wireless | JPWL (wireless applications) | |

| Part 12 | ISO/IEC 15444-12 | 2004 | 2008[16] | ISO base media file format | |||

| Part 13 | ISO/IEC 15444-13 | 2008 | 2008[17] | T.812 | An entry level JPEG 2000 encoder | ||

| Part 14 | under development[18][19] | XML structural representation and reference | JPXML[20] |

Technical discussion

The aim of JPEG 2000 is not only improving compression performance over JPEG but also adding (or improving) features such as scalability and editability. JPEG 2000's improvement in compression performance relative to the original JPEG standard is actually rather modest and should not ordinarily be the primary consideration for evaluating the design. Very low and very high compression rates are supported in JPEG 2000. The ability of the design to handle a very large range of effective bit rates is one of the strengths of JPEG 2000. For example, to reduce the number of bits for a picture below a certain amount, the advisable thing to do with the first JPEG standard is to reduce the resolution of the input image before encoding it. That's unnecessary when using JPEG 2000, because JPEG 2000 already does this automatically through its multiresolution decomposition structure. The following sections describe the algorithm of JPEG 2000.

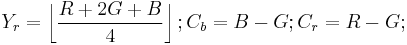

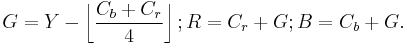

Color components transformation

Initially, images have to be transformed from the RGB color space to another color space, leading to three components that are handled separately. There are two possible choices:

- Irreversible Color Transform (ICT) uses the well known YCBCR color space. It is called "irreversible" because it has to be implemented in floating or fix-point and causes round-off errors.

- Reversible Color Transform (RCT) uses a modified YUV color space that does not introduce quantization errors, so it is fully reversible. Proper implementation of the RCT requires that numbers are rounded as specified that cannot be expressed exactly in matrix form. The transformation is:

and

The chrominance components can be, but do not necessarily have to be, down-scaled in resolution; in fact, since the wavelet transformation already separates images into scales, downsampling is more effectively handled by dropping the finest wavelet scale. This step is called multiple component transformation in the JPEG 2000 language since its usage is not restricted to the RGB color model.

Tiling

After color transformation, the image is split into so-called tiles, rectangular regions of the image that are transformed and encoded separately. Tiles can be any size, and it is also possible to consider the whole image as one single tile. Once the size is chosen, all the tiles will have the same size (except optionally those on the right and bottom borders). Dividing the image into tiles is advantageous in that the decoder will need less memory to decode the image and it can opt to decode only selected tiles to achieve a partial decoding of the image. The disadvantage of this approach is that the quality of the picture decreases due to a lower peak signal-to-noise ratio. Using many tiles can create a blocking effect similar to the older JPEG 1992 standard.

Wavelet transform

These tiles are then wavelet transformed to an arbitrary depth, in contrast to JPEG 1992 which uses an 8×8 block-size discrete cosine transform. JPEG 2000 uses two different wavelet transforms:

- irreversible: the CDF 9/7 wavelet transform. It is said to be "irreversible" because it introduces quantization noise that depends on the precision of the decoder.

- reversible: a rounded version of the biorthogonal CDF 5/3 wavelet transform. It uses only integer coefficients, so the output does not require rounding (quantization) and so it does not introduce any quantization noise. It is used in lossless coding.

The wavelet transforms are implemented by the lifting scheme or by convolution.

Quantization

After the wavelet transform, the coefficients are scalar-quantized to reduce the number of bits to represent them, at the expense of quality. The output is a set of integer numbers which have to be encoded bit-by-bit. The parameter that can be changed to set the final quality is the quantization step: the greater the step, the greater is the compression and the loss of quality. With a quantization step that equals 1, no quantization is performed (it is used in lossless compression).

Coding

The result of the previous process is a collection of sub-bands which represent several approximation scales. A sub-band is a set of coefficients—real numbers which represent aspects of the image associated with a certain frequency range as well as a spatial area of the image.

The quantized sub-bands are split further into precincts, rectangular regions in the wavelet domain. They are typically selected in a way that the coefficients within them across the sub-bands form approximately spatial blocks in the (reconstructed) image domain, though this is not a requirement.

Precincts are split further into code blocks. Code blocks are located in a single sub-band and have equal sizes—except those located at the edges of the image. The encoder has to encode the bits of all quantized coefficients of a code block, starting with the most significant bits and progressing to less significant bits by a process called the EBCOT scheme. EBCOT here stands for Embedded Block Coding with Optimal Truncation. In this encoding process, each bit plane of the code block gets encoded in three so-called coding passes, first encoding bits (and signs) of insignificant coefficients with significant neighbors (i.e., with 1-bits in higher bit planes), then refinement bits of significant coefficients and finally coefficients without significant neighbors. The three passes are called Significance Propagation, Magnitude Refinement and Cleanup pass, respectively.

Clearly, in lossless mode all bit planes have to be encoded by the EBCOT, and no bit planes can be dropped.

The bits selected by these coding passes then get encoded by a context-driven binary arithmetic coder, namely the binary MQ-coder. The context of a coefficient is formed by the state of its nine neighbors in the code block.

The result is a bit-stream that is split into packets where a packet groups selected passes of all code blocks from a precinct into one indivisible unit. Packets are the key to quality scalability (i.e., packets containing less significant bits can be discarded to achieve lower bit rates and higher distortion).

Packets from all sub-bands are then collected in so-called layers. The way the packets are built up from the code-block coding passes, and thus which packets a layer will contain, is not defined by the JPEG 2000 standard, but in general a codec will try to build layers in such a way that the image quality will increase monotonically with each layer, and the image distortion will shrink from layer to layer. Thus, layers define the progression by image quality within the code stream.

The problem is now to find the optimal packet length for all code blocks which minimizes the overall distortion in a way that the generated target bitrate equals the demanded bit rate.

While the standard does not define a procedure as to how to perform this form of rate–distortion optimization, the general outline is given in one of its many appendices: For each bit encoded by the EBCOT coder, the improvement in image quality, defined as mean square error, gets measured; this can be implemented by an easy table-lookup algorithm. Furthermore, the length of the resulting code stream gets measured. This forms for each code block a graph in the rate–distortion plane, giving image quality over bitstream length. The optimal selection for the truncation points, thus for the packet-build-up points is then given by defining critical slopes of these curves, and picking all those coding passes whose curve in the rate–distortion graph is steeper than the given critical slope. This method can be seen as a special application of the method of Lagrange multiplier which is used for optimization problems under constraints. The Lagrange multiplier, typically denoted by λ, turns out to be the critical slope, the constraint is the demanded target bitrate, and the value to optimize is the overall distortion.

Packets can be reordered almost arbitrarily in the JPEG 2000 bit-stream; this gives the encoder as well as image servers a high degree of freedom.

Already encoded images can be sent over networks with arbitrary bit rates by using a layer-progressive encoding order. On the other hand, color components can be moved back in the bit-stream; lower resolutions (corresponding to low-frequency sub-bands) could be sent first for image previewing. Finally, spatial browsing of large images is possible through appropriate tile and/or partition selection. All these operations do not require any re-encoding but only byte-wise copy operations.

Performance

Compared to the previous JPEG standard, JPEG 2000 delivers a typical compression gain in the range of 20%, depending on the image characteristics. Higher-resolution images tend to benefit more, where JPEG-2000's spatial-redundancy prediction can contribute more to the compression process. In very low-bitrate applications, studies have shown JPEG 2000 to be outperformed[21] by the intra-frame coding mode of H.264. Good applications for JPEG 2000 are large images, images with low-contrast edges — e.g., medical images.

File format and code stream

Similar to JPEG-1, JPEG 2000 defines both a file format and a code stream. Whereas the latter entirely describes the image samples, the former includes additional meta-information such as the resolution of the image or the color space that has been used to encode the image. JPEG 2000 images should — if stored as files — be boxed in the JPEG 2000 file format, where they get the .jp2 extender. The part-2 extension to JPEG 2000, i.e., ISO/IEC 15444-2, also enriches this file format by including mechanisms for animation or composition of several code streams into one single image. Images in this extended file-format use the .jpx extension.

There is no standardized extension for code-stream data because code-stream data is not to be considered to be stored in files in the first place, though when done for testing purposes, the extension .jpc or .j2k appear frequently.

Metadata

For traditional JPEG, additional metadata, e.g. lighting and exposure conditions, is kept in an application marker in the Exif format specified by the JEITA. JPEG 2000 chooses a different route, encoding the same metadata in XML form. The reference between the Exif tags and the XML elements is standardized by the ISO TC42 committee in the standard 12234-1.4.

Extensible Metadata Platform can also be embedded in JPEG 2000.

Applications of JPEG 2000

Some markets and applications intended to be served by this standard are listed below:

- Consumer applications such as multimedia devices (e.g., digital cameras, personal digital assistants, 3G mobile phones, color facsimile, printers, scanners, etc.)

- Client/server communication (e.g., the Internet, Image database, Video streaming, video server, etc.)

- Military/surveillance (e.g., HD satellite images, Motion detection, network distribution and storage, etc.)

- Medical imagery, esp. the DICOM specifications for medical data interchange.

- Remote sensing

- High-quality frame-based video recording, editing and storage.

- Live HDTV feed contribution (I-frame only video compression with low transmission latency), such as live HDTV feed of a sport event linked to the TV station studio

- Digital cinema

- JPEG 2000 has many design commonalities with the ICER image compression format that is used to send images back from the Mars rovers.

- World Meteorological Organization has built JPEG 2000 Compression into the new GRIB2 file format. The GRIB file structure is designed for global distribution of meteorological data. The implementation of JPEG 2000 compression in GRIB2 has reduced file sizes up to 80%.[22]

Comparison with PNG

Although JPEG 2000 format supports lossless encoding, it is not intended to completely supersede today's dominant lossless image file formats.

The PNG (Portable Network Graphics) format is still more space-efficient in the case of images with many pixels of the same color, such as diagrams, and supports special compression features that JPEG 2000 does not.

Legal issues

JPEG 2000 is by itself licensed, but the contributing companies and organizations agreed that licenses for its first part—the core coding system—can be obtained free of charge from all contributors.

The JPEG committee has stated:

- It has always been a strong goal of the JPEG committee that its standards should be implementable in their baseline form without payment of royalty and license fees... The up and coming JPEG 2000 standard has been prepared along these lines, and agreement reached with over 20 large organizations holding many patents in this area to allow use of their intellectual property in connection with the standard without payment of license fees or royalties.[23]

However, the JPEG committee has also noted that undeclared and obscure submarine patents may still present a hazard:

- It is of course still possible that other organizations or individuals may claim intellectual property rights that affect implementation of the standard, and any implementers are urged to carry out their own searches and investigations in this area.[24]

Because of this statement, controversy remains in the software community concerning the legal status of the JPEG 2000 standard.

However, many Linux distributions include a JPEG 2000 library.[25]

Related standards

Several additional parts of the JPEG 2000 standard exist; Amongst them are ISO/IEC 15444-2:2000, JPEG 2000 extensions defining the .jpx file format, featuring for example Trellis quantization, an extended file format and additional color spaces,[26] ISO/IEC 15444-4:2000, the reference testing and ISO/IEC 15444-6:2000, the compound image file format (.jpm), allowing compression of compound text/image graphics.[27]

Extensions for secure image transfer, JPSEC (ISO/IEC 15444-8), enhanced error-correction schemes for wireless applications, JPWL (ISO/IEC 15444-11) and extensions for encoding of volumetric images, JP3D (ISO/IEC 15444-10) are also already available from the ISO.

JPIP protocol for streaming JPEG 2000 images

In 2005, a JPEG 2000 based image browsing protocol, called JPIP has been published as ISO/IEC 15444-9.[28] Within this framework, only selected regions of potentially huge images have to be transmitted from an image server on the request of a client, thus reducing the required bandwidth.

JPEG 2000 data may also be streamed using the ECWP and ECWPS protocols found within the ERDAS ECW/JP2 SDK.

Motion JPEG 2000

Motion JPEG 2000 is defined in ISO/IEC 15444-3 and in ITU-T T.802.[29] It specifies the use of the JPEG 2000 format for timed sequences of images (motion sequences), possibly combined with audio, and composed into an overall presentation.[30][31] It also defines a file format,[32] based on ISO base media file format (ISO 15444-12). Filename extensions for Motion JPEG 2000 video files are .mj2 and .mjp2 according to RFC 3745.

Motion JPEG 2000 (often referenced as MJ2 or MJP2) also is under consideration as a digital archival format by the Library of Congress. It is an open ISO standard and an advanced update to MJPEG (or MJ), which was based on the legacy JPEG format. Unlike common video formats, such as MPEG-4 Part 2, WMV, and H.264, MJ2 does not employ temporal or inter-frame compression. Instead, each frame is an independent entity encoded by either a lossy or lossless variant of JPEG 2000. Its physical structure does not depend on time ordering, but it does employ a separate profile to complement the data. For audio, it supports LPCM encoding, as well as various MPEG-4 variants, as "raw" or complement data.[33][34]

ISO base media file format

ISO/IEC 15444-12 is identical with ISO/IEC 14496-12 (MPEG-4 Part 12) and it defines ISO base media file format. For example, Motion JPEG 2000 file format, MP4 file format or 3GP file format are also based on this ISO base media file format.[35][36][37][38][39]

GML JP2 Georeferencing

The Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC) has defined a metadata standard for georeferencing JPEG 2000 images with embedded XML using the Geography Markup Language (GML) format: GML in JPEG 2000 for Geographic Imagery Encoding (GMLJP2), version 1.0.0, dated 2006-01-18.[40]

JP2 and JPX files containing GMLJP2 markup can be located and displayed in the correct position on the Earth's surface by a suitable Geographic Information System (GIS), in a similar way to GeoTIFF images.

Application support

Applications

- ^ a b basic and advanced support refer to conformance with, respectively, Part1 and Part2 of the JPEG 2000 Standard.

- ^ Adobe Photoshop CS2 and CS3's official JPEG 2000 plug-in package is not installed by default and must be manually copied from the install disk/folder to the Plug-Ins > File Formats folder.

- ^ a b IrfanView's official plug-in package supports reading of .jp2 files but writing is quite limited until plug-in is purchased separately.

- ^ Mozilla support for JPEG 2000 was requested in April 2000, but the report was closed as WONTFIX in August 2009.[1] JPEG 2000 support is available as a plugin for Windows[2] and Linux[3], there's a extension that adds support to older versions of Firefox.[4]

- ^ XnView supports JPEG 2000 compression only in MS Windows version

Libraries

| Program | Basic | Advanced | Language | License | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Read | Write | Read | Write | |||

| ERDAS ECW JPEG2000 SDK | Yes | Yes | ? | ? | C/C++ | Proprietary |

| FFmpeg | Yes [Note 1] | Yes [Note 1] | ? | ? | C | LGPL |

| GTK+ (from 2.14) | Yes | No | ? | No | C/GTK | LGPL |

| J2K-Codec | Yes | No | Yes | No | C++ | Proprietary |

| JasPer | Yes | Yes | No | No | C | MIT License-style |

| Kakadu | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | C++ | Proprietary |

| OpenJPEG | Yes | Yes | ? | ? | C | BSD |

See also

- Comparison of graphics file formats

- DjVu – a compression format that also uses wavelets and that is designed for use on the web.

- ECW – a wavelet compression format that compares well to JPEG 2000.

- High bit rate audio video over Internet Protocol

- QuickTime – a multimedia framework, application and web browser plugin developed by Apple, capable of encoding, decoding and playing various multimedia files (including JPEG 2000 images by default).

- MrSID – a wavelet compression format that compares well to JPEG 2000

- PGF – a fast wavelet compression format that compares well to JPEG 2000

- JPIP – JPEG 2000 Interactive Protocol

Notes

- ^ The JPEG Still Picture Compression Standard pp.6-7

- ^ a b JPEG. "Joint Photographic Experts Group, JPEG2000". http://www.jpeg.org/jpeg2000/index.html. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ^ IGN Standardization Team. "JPEG2000 (ISO 15444)". http://eden.ign.fr/std/JPEG2000/index_html. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ^ ISO. "ISO/IEC 15444-1:2004 - Information technology -- JPEG 2000 image coding system: Core coding system". http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_ics/catalogue_detail_ics.htm?csnumber=27687. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ^ ISO. "ISO/IEC 15444-2:2004 - Information technology -- JPEG 2000 image coding system: Extensions". http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=33160. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ^ ISO. "ISO/IEC 15444-3:2007 - Information technology -- JPEG 2000 image coding system: Motion JPEG 2000". http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=41570. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ^ ISO. "ISO/IEC 15444-4:2004 - Information technology -- JPEG 2000 image coding system: Conformance testing". http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=39079. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ^ ISO. "ISO/IEC 15444-5:2003 - Information technology -- JPEG 2000 image coding system: Reference software". http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=33877. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ^ ISO. "ISO/IEC 15444-6:2003 - Information technology -- JPEG 2000 image coding system -- Part 6: Compound image file format". http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=35458. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ^ ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 29/WG 1 (2000-12-08). "JPEG, JBIG - Resolutions of 22nd WG1 New Orleans Meeting" (DOC). http://www.itscj.ipsj.or.jp/sc29/open/29view/29n39731.doc. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ^ "22nd WG1 New Orleans Meeting, Draft Meeting Report" (DOC). 2000-12-08. http://www.itscj.ipsj.or.jp/sc29/open/29view/29n39741.doc. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ^ ISO. "ISO/IEC 15444-8:2007 - Information technology -- JPEG 2000 image coding system: Secure JPEG 2000". http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=37382. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ^ ISO. "ISO/IEC 15444-9:2005 - Information technology -- JPEG 2000 image coding system: Interactivity tools, APIs and protocols". http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=39413. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ^ ISO. "ISO/IEC 15444-10:2008 - Information technology -- JPEG 2000 image coding system: Extensions for three-dimensional data". http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=40024. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ^ ISO. "ISO/IEC 15444-11:2007 - Information technology -- JPEG 2000 image coding system: Wireless". http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=40025. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ^ ISO. "ISO/IEC 15444-12:2008 - Information technology -- JPEG 2000 image coding system -- Part 12: ISO base media file format". http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=51537. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ^ ISO. "ISO/IEC 15444-13:2008 - Information technology -- JPEG 2000 image coding system: An entry level JPEG 2000 encoder". http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=42271. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ^ ISO (2007-07-01). "ISO/IEC AWI 15444-14 - Information technology -- JPEG 2000 image coding system -- Part 14: XML structural representation and reference". http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=50410. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ^ ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 29/WG 1 (2009-01-23). "Resolutions of 47th WG1 San Francisco Meeting" (DOC). http://www.itscj.ipsj.or.jp/sc29/open/29view/29n100261.doc. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ^ "Resolutions of 41st WG1 San Jose Meeting" (DOC). 2007-04-27. http://www.itscj.ipsj.or.jp/sc29/open/29view/29n83811.doc. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ^ Halbach, Till (July 2002). "Performance comparison: H.26L intra coding vs. JPEG2000". http://etill.net/papers/jvt-d039.pdf. Retrieved 2008-04-22.

- ^ wgrib2 home page

- ^ JPEG 2000 Concerning recent patent claims

- ^ JPEG 2000 Committee Drafts

- ^ OpenJPEG package in Ubuntu, OpenSUSE, Debian, Arch, Mandriva

- ^ International Organization for Standardization (2004). "ISO/IEC 15444-2:2004, Information technology -- JPEG 2000 image coding system: Extensions". http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=33160. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ^ International Organization for Standardization (2003). "ISO/IEC 15444-6:2003, Information technology -- JPEG 2000 image coding system -- Part 6: Compound image file format". http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=35458. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ^ International Organization for Standardization (2005). "ISO/IEC 15444-9:2005, Information technology -- JPEG 2000 image coding system: Interactivity tools, APIs and protocols". http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=39413. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ^ "T.802 : Information technology - JPEG 2000 image coding system: Motion JPEG 2000". 2005-01. http://www.itu.int/rec/T-REC-T.802/en. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ^ International Organization for Standardization (2007). "ISO/IEC 15444-3:2007, Information technology -- JPEG 2000 image coding system: Motion JPEG 2000". http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=41570. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ^ JPEG (2007). "Motion JPEG 2000 (Part 3)". http://www.jpeg.org/jpeg2000/j2kpart3.html. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ^ ITU-T. "T.802 : Information technology – JPEG 2000 image coding system: Motion JPEG 2000 - Summary". http://www.itu.int/dms_pubrec/itu-t/rec/t/T-REC-T.802-200501-I!!SUM-HTM-E.htm. Retrieved 2010-09-28.

- ^ Motion JPEG 2000 (Part 3)

- ^ Motion JPEG 2000 mj2 File Format. Sustainability of Digital Formats Planning for Library of Congress Collections.

- ^ ISO (2006-04). ISO Base Media File Format white paper - Proposal. archive.org. Archived from the original on 2008-07-14. http://web.archive.org/web/20080714101745/http://www.chiariglione.org/mpeg/technologies/mp04-ff/index.htm. Retrieved 2009-12-26.

- ^ ISO (2005-10). MPEG-4 File Formats white paper - Proposal. archive.org. Archived from the original on 2008-01-15. http://web.archive.org/web/20080115035235/http://www.chiariglione.org/mpeg/technologies/mp04-ff/index.htm. Retrieved 2009-12-26.

- ^ ISO (2009-10). ISO Base Media File Format white paper - Proposal. chiariglione.org. http://mpeg.chiariglione.org/technologies/mpeg-4/mp04-ff/index.htm. Retrieved 2009-12-26.

- ^ International Organization for Standardization (2004). "ISO/IEC 14496-12:2004, Information technology -- Coding of audio-visual objects -- Part 12: ISO base media file format". http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=38539. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ^ International Organization for Standardization (2008). "ISO/IEC 15444-12:2008, Information technology -- JPEG 2000 image coding system -- Part 12: ISO base media file format". http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=51537. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ^ Open Geospatial Consortium GMLJP2 Home Page

- ^ "Blender 2.49". 2009-05-30. http://www.blender.org/development/release-logs/blender-249/. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- ^ "The digiKam Handbook - Supported File Formats". docs.kde.org. http://docs.kde.org/development/en/extragear-graphics/digikam/using-fileformatsupport.html. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- ^ "The Showfoto Handbook - Supported File Formats". http://docs.kde.org/development/en/extragear-graphics/showfoto/using-fileformatsupport.html. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- ^ a b c "Development/Architecture/KDE3/Imaging and Animation". http://techbase.kde.org/Development/Architecture/KDE3/Imaging_and_Animation. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- ^ The GIMP Team (2009-08-16). "GIMP 2.7 RELEASE NOTES". http://www.gimp.org/release-notes/gimp-2.7.html. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

References

- Official JPEG 2000 page

- Final Committee Drafts of JPEG 2000 standard (as the official JPEG 2000 standard is not freely available, the final drafts are the most accurate freely available documentation about this standard)

- Gormish Notes on JPEG 2000

- Technical overview of JPEG 2000 (PDF)

- Everything you always wanted to know about JPEG 2000 - published by intoPIX in 2008 (PDF)

External links

- RFC 3745, MIME Type Registrations for JPEG 2000 (ISO/IEC 15444)

- Official JPEG 2000 website

- All published books about JPEG 2000

- JPEG 2000 comparisons

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||